by Diane Rufino, January 3, 2019

Let me add that a bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inference……” – Thomas Jefferson, in a letter to James Madison, December 20, 1787

December 15 marks a very special day in our founding history – On that date in 1791, the first 14 states (Vermont had just been admitted to the Union as the 14th state), ratified the first 10 amendments to the US Constitution, known collectively as our Bill of Rights. We often take it for granted that these first ten amendments, our Bill of Rights, are included in our Constitution, but if we want to point to one reason the colonies went to war for their independence from Great Britain, it was to permanently secure the rights embodied in our Bill of Rights from all reaches of government. Without the Bill of Rights, the revolution would have been in vein. Thomas Jefferson, probably the Founder who exerted the most pressure on James Madison for a Bill of Rights, advised: “A bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no just government should refuse.” He wrote this to Madison on December 20, 1787, almost three months after the Constitution had been signed by its drafters in Philadelphia.

On Bill of Rights Day, we reflect upon those rights guaranteed in the first nine amendments (the tenth being a restatement of federalism – the strict separation of power between the federal government and the States) but more importantly, we should come to appreciate the efforts of certain particularly liberty-minded Founders who fought against great odds to make sure that our Constitution in fact included a Bill of Rights. After all, James Madison, considered the Constitution’s author, and most of the other Federalists did not see the need for a Bill of Rights and thought the Constitution wholly sufficient without it. That was the status of the Constitution when it went to the states for ratification.

What is a “Bill of Rights”? A bill of rights, sometimes called a Declaration of Rights or a Charter of Rights, is a list of the most important rights belonging to the citizens of a country – rights that the King or other form of government must respect. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement either by law or by conduct from public officials. The US Bill of Rights is the Declaration and enumeration is the individual rights memorialized in the Constitution intended to protect the individual against violations and abuses of power by the government. In that respect, our Bill of Rights is like most other bill of rights (including the English Bill of Rights is 1689 and the great Magna Carta of 1215). This history of England, including the movement of groups of people (like the Puritans and Pilgrims), to the New World, is a history continually seeking for the recognition and security of fundamental human liberties. And early colonial history continued that tradition of setting out the rights and privileges of the individual in their government charters.

The Preamble to the Bill of Rights explains its clear purpose. It reads: “The Conventions of a number of the States having at the time of their adopting the Constitution, expressed a desire, in order to prevent misconstruction or abuse of its powers, that further declaratory and restrictive clauses should be added: And as extending the ground of public confidence in the Government, will best insure the beneficent ends of its institution.”

In other words, the Bill of Rights is a further limitation on the power of government, above and beyond those limitations already imposed by its very design and delegation of limited powers.

HISTORY:

Again, a Bill of Rights (or Declaration of Rights, or Charter of Rights), is a list of the most important rights belonging to the citizens of a country that the King or other form of government must respect. Bills of rights may be “entrenched” or “unentrenched.” A bill of rights that is “entrenched” cannot be amended or repealed by the governing legislature through regular procedure, but rather, it would require a supermajority or referendum. Bills of rights that are “entrenched” are often those which are part of a country’s constitution, and therefore subject to special procedures applicable to constitutional amendments. A bill of rights that is not entrenched (“unentrenched”) is merely statutory in form and as such can be modified or repealed by the legislature at will.

The history of the world shows that there have been limited instances where the rights of the people have been enumerated and/or protected by a Bill of Rights. This history includes the following charters, documents, or bills of right:

- Magna Carta (1215; England) rights for barons

- Great Charter of Ireland (1216; Ireland) rights for barons – Ireland became independent of Great Britain in 1937

- Golden Bull of 1222 (1222; Hungary) rights for nobles – which interestingly, included the right of Nullification

- Charter of Kortenberg (1312; Belgium) rights for all citizens “rich and poor”

- Twelve Articles (1525; Germany) – considered the first draft of human rights and civil liberties in continental Europe after the Roman Empire.

- Petition of Right (1628; England)

- English Bill of Rights 1689

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789; France) – inspired by Thomas Jefferson

- The US Bill of Rights (1791)

The roots of our modern-day liberty originated in England, as far back as 1100, culminating there with the English Bill of Rights in 1689 and ultimately providing the blueprint for our very own US Bill of Rights in 1791. The roots of liberty, including the roots of our very own American liberty rights, can be found in the selection of charters and documents listed below:

- The 1100 Charter of Liberties (also called the Coronation Charter) – The 1100 Charter of Liberties was a written proclamation offered by Henry I of England and issued upon his accession to the throne in 1100. It sought to bind the King to certain laws regarding the treatment of nobles, church officials, and individuals – most notably, certain marriage rights, rights of inheritance, amnesty rights, rights for the criminally-accused, and environmental protection (forests). It is considered to be the precursor to the Magna Carta.

- The Magna Carta of 1215 (“the Great Charter”) – The barons at the time, frustrated by ten years of excessive taxation by King John in order to finance a campaign to regain lands in France only to watch the King return home in defeat, consolidated their power and threatened to renounce him. Over the next eight months, they made repeated demands to the King, requesting that he give them a guarantee that he would observe their rights. But these negotiations amounted to nothing. And so, on May 5, 1215, the barons gathered and agreed to declare war on him. On May 17, the barons captured London, the largest town in England, without a fight, and finally, King John took notice. With London lost and ever more supporters flocking to the side of the barons, he sent word that he would meet with them to discuss terms of peace.. Over the next few days, the barons assembled in great numbers on the fields of Runnymede, a relatively obscure meadow that lies between the town of Staines and Windsor castle, where King John was based. Negotiations took place over the next several days and finally, on June 15, King John affixed his seal to the document that would become known as the Magna Carta (or “The Great Charter”). The Magna Carta enumerated an expansive list (63 “chapters”) of rights for barons, and also provided the remedy of Nullification. The principles extended beyond the often-recognized origin of the “No Taxation Without Representation” doctrine in chapter 12 (and hence the creation of a “people’s body” which addressed matters of taxation and spending) and the Due Process clause of chapter 39. The concepts of “Trial by Jury” and “No Cruel Punishments” are present in chapter 21; and the forerunner of the “Confrontation Clause” of our 6th Amendment addressed in chapters 38, 40, and 44. But the most important contribution of the Magna Carta is the claim that there is a fundamental set of principles which even the King must respect. Above all else, Magna Carta makes the case that the people have a “right” to expect boundaries from the King in their lives and with respect to their property. They have a right to expect “reasonable” conduct. [King John would go on to ignore the promises he made in signing the Magna Carta]

- The Petition of Right of 1628 – In 1628, under the leadership of Sir Edward Coke, a legal scholar-turned-practical politician, Parliament petitioned Charles I, son of the recently deceased King James I, to uphold the traditional rights of Englishmen, as set forth in the Magna Carta. It was an appeal to his sense of being a just King. Charles was already on his way to being a notorious tyrant. Parliament was not only fed up with is participation in the Thirty Years War (a highly destructive European war) against its consent, but when it refused to provide Charles the revenue to fight the war, he dissolved the body (several times, actually). That would lead Charles to raise revenue other ways – by gathering “forced loans” and “ship money” without Parliamentary approval (hence, taxation without representation in violation of the Magna Carta) and arbitrarily imprisoning those who refused to pay. Among the customary “diverse rights and liberties of the subjects” listed in the Petition of Right were no taxation without consent (as mentioned), “due process of law,” the right to habeas corpus, no quartering of troops, the respect for private property, and the imposition of no cruel punishment. King Charles did not consider himself bound by the Petition and so, he simply disregarded it. He would later be officially tried for high treason by a rump Parliament and beheaded in 1649. [The Petition of Right would have a profound effect on our US Bill of Rights: The Due Process clause of the 5th Amendment, the “Criminal Trials” clause of the 6th Amendment, and the “Civil Jury Trial” clause of the 7th Amendment all are influenced by the Petition of Right. Furthermore, during the 1760s, the American colonists articulated their grievances against King George in terms similar to those used by Lord Coke in the Petition of Right to uphold the rights of Englishmen].

- The English Bill of Rights of 1689 – After the Bloodless Revolution or “Glorious Revolution” (in which the English Parliament instigated a bloodless coup, replacing King James II with his daughter, Mary II and her husband, William III), Parliament set to right the abuses of its previous kings – Charles I, Charles II, and James II. It drafted and adopted a bill of rights, known as the English Bill of Rights, as which set out certain basic civil rights and clarified the right of secession for the British Crown. It was presented to William and Mary in February 1689 as a condition to the offer to become joint ruling sovereigns of England. It was contractual in nature so that the acceptance of the throne was tied to their express promise to recognize the rights set forth in the Bill of Rights. A violation of that agreement would terminate the right of William and Mary to rule. The Bill of Rights lays down limits on the powers of the monarch and sets out the rights of Parliament. It further, and most importantly for this discussion, sets out certain rights of the individual, including: the right to bear arms for self-defense, the right of Due Process, the right to petition government, such criminal defense rights as the right to be free from excessive bail, the right to a jury trial for the crime of high treason, and the right against any cruel and/or unusual punishment, the guarantee that there would be no taxation without representation, the right to be free of a standing army in times of peace, and the right to be free of any quartering of troops. [Great Britain is unlike the United States in that it has no formal Constitution; rather, the English Bill of Rights, taken together with the Magna Carta, the Petition of Right, the Habeas Corpus Act 1679 and the Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949 are considered, in total, as the uncodified British constitution].

- The colonies being organized under grants and agreements from England, it was assumed that English traditions applied. The colonists considered themselves British subjects and as such, they believed they were entitled to all the rights and privileges of Englishmen. That is why they reacted as they did to the taxes imposed by Parliament, why one protest theme was “No Taxation Without Representation,” why the Sons of Liberty formed, why they harassed the colonial stamp collectors and stamp masters until they resigned, why they engaged in acts of civil disobedience (such as preventing the British from unloading their ships at colonial ports) or hanging colonial governors in effigy, why they tossed crates of tea into the Boston Harbor, why men like Patrick Henry called for the raising and training of colonial militias, and why they were willing to confront the Redcoats with their muskets when they sought to destroy the stockpiles of colonial ammunition. It seemed that once again, as English history has shown true, Englishmen would have to exert their rights and demand that the King to respect them. Proper boundaries would once again have to be established.

- King John’s rejection of the Magna Carta (1215) and King Charles’s rejection of the Petition of Right (1628) proved to our Founding Fathers that the system established in Great Britain provided only arbitrary security for individual rights. They would need to come up with a different system of government, grounded on more “enlightened” principles and “enlightened” government philosophy. And that is exactly what they did in the Declaration of Independence – announcing that the American states were united on the concept of Individual Sovereignty, that government power originated from the People, to serve the People, and not from kings (“the Divine Right of Kings”) to serve kings.

With what many believe to be divine guidance and protection, the thirteen original colonies fought and won their independence from Great Britain in 1781. Lord Cornwallis surrendered his British troops to General George Washington, Commander of the Continental Army, on October 19, 1781 and the Treaty of Paris, signed in September 1783, marked the official end of the struggle. Since the colonies worked together in a collaborative effort to communicate grievances and concerns to King George and Parliament and to engage in a concerted effort to prevent war, but then once war came, to fight and manage the war effort, it seemed only natural to continue to collaborate in their independence. The first attempt at a loose union of states, under the Articles of Confederation, was not very successful. The government lacked the enforcement power needed to effectively act on behalf of the states, such as the power to collect revenue to pay the war debt.

Taking note of the limitations of the common government (the Confederation Congress, aka, Congress of the Confederation, or sometimes even referred to still as the Continental Congress), certain members of our founding generation instigated for a Convention to amend that government. Eventually, in February 1787, Congress called for such a Convention to meet in May in Philadelphia “to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Federal Government [the Articles of Confederation] adequate to the exigencies of the Union.” And so, the Convention did convene on May 25, 1787 in Philadelphia with delegates from all the states except Rhode Island. The Constitutional Convention, as it came to be known, quickly changed direction – from amending the Articles of Confederation to designing an altogether different form of government. James Madison would be the architect of that plan (the Virginia Plan). The collective wisdom of the delegates at the Convention identified the weakness of the Virginia Plan, which for the colonies was the creation of a “national” government, with concentrated power in that government, rather than a “federal” government which left most of the sovereign power with the states. A federal government, with the sovereignty of the States keeping the sovereign power of the federal government in check, was the form of government that the delegates preferred. A government that could remain checked against abuses was one that honored the fiercely independent and freedom-loving nature of the colonies and one which would address the reasons for the revolution against Great Britain.

In the summer of 1787, delegates from the 13 states convened in Philadelphia and drafted a remarkable blueprint for self-government — the Constitution of the United States. The first draft set up a system of checks and balances that included a strong executive branch, a representative legislature and a federal judiciary.

The Constitution was remarkable, but deeply flawed. For one thing, it did not include a specific declaration – or bill – of individual rights. As it turned out, and luckily for us as depositories of certain “inalienable rights” as well as civil rights (those belonging to individuals living in a society, subject to the rule of law), the lack of a Bill of Rights turned out to be an obstacle to the Constitution’s ratification by the states that could not be overcome. The Federalists opposed including a bill of rights on the ground that it was unnecessary. According to James Madison, a leading Federalist, a Bill of Rights was not necessary, arguing that because the general government was one of limited powers, having only those powers specifically delegated to it and none touching on individual rights. Besides, he said, a Bill of Rights would only create confusion (inferring that any other right or privilege not listed in the Bill of Rights would be fair game for federal regulation) and also, state governments could ensure these freedoms without the need for a federal mandate. The Anti-Federalists, who were afraid of a strong centralized government and knowing that history has clearly shown that governments tend to concentrate power and tend towards centralization and then tyranny/abuse, refused to support the Constitution without one.

At the close of the Philadelphia Convention, on September 20, 1787, the delegates left with mixed feelings about the document they drafted. Of the 55 delegates to the Convention, only 39 signed it. Of the 16 that did not sign, some left early (for business, health reasons, family concerns, or out of protest) and some refused to sign out of protest. Some of the more important delegates (ie, position and/or influence in their states) who refused to sign were the following: George Mason of Virginia (because it did not contain a Bill of Rights), Luther Martin of Maryland (because it violated states’ rights), John Mercer of Maryland (because it did not contain a Bill of Rights), Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts (because it did not contain a Bill of Rights), John Lansing and Robert Yates, both of New York (because it created too strong of a government, which he characterized as much more “national” than “federal”), and Edmund Randolph of Virginia (because it contained insufficient checks and balances to prevent government abuse). Had some of our most active and influential founding fathers attended the Convention, there would have been far greater opposition to the final product. Those who refused to attend or who were unable to included: Patrick Henry (refused to attend, he “smelled a rat” who he believed would try to vest the common government with too much power), Richard Henry Lee (refused to attend because he too didn’t trust the motives of those who called it), Thomas Jefferson (was acting as Ambassador to France at the time, but offered to advise the delegates by correspondence), John Adams (was acting as Ambassador to Great Britain at the time), Samuel Adams (refused to attend because he rejected the purpose of the Convention) and John Hancock (refused to attend for the same reason as Sam Adams).

Many of those who refused to sign the Constitution vowed to fight its ratification at the state conventions – George Mason, Elbridge Gerry, the delegates from Maryland, Luther Martin and John Mercer, and the delegates from New York, John Lansing and Robert Yates. And some strong anti-Federalists who were not delegates at Philadelphia would oppose it as well –Richard Henry Lee, Sam Adams, John Hancock, James Monroe (Virginia), and New York’s Governor George Clinton (who wrote several anti-Federalist essays under the pen name “Cato”). Add to these “big guns” the biggest ones of all – Thomas Jefferson, who was as strong a proponent of a Bill of Rights as one could be, and Patrick Henry, perhaps our most vocal and passionate orator for liberty. Jefferson would have advised Madison to include one, and certainly would have taken issue with Madison’s position on the matter, even though he would have had to do so by correspondence. Perhaps that is the reason why Madison lapsed during the final days of the Convention in updating Jefferson as to the discussions and decisions made in the Convention. It wasn’t until a month after the Convention wrapped up, on October 24, that he finally wrote to him again and sent him a copy of the draft Constitution. We do know that as the debate intensified over a Bill of Rights, Jefferson wrote Madison with his strong opinion, including his letter of December 20, 1787, in which he wrote: “A bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no just government should refuse.” [The Appendix at the end of this article contains the full commentary in Jefferson’s letter relating to the lack of Bill of Rights in the new Constitution].

On September 28, 1787, the Confederation Congress (aka, Congress of the Confederation) advised the states to begin calling their ratifying conventions, and several did so immediately. Madison left the Philadelphia Convention uncertain what the outcome of the ratification process would be. The dissent by Edmund Randolph and George Mason, both from his home state, and then their refusal to attach their names to the Constitution weighed very heavily on his mind. As Kevin Gutzman pointed out in his book James Madison and the Making of America, the influence that those two men alone had in the overall ratification process potentially could more than counter the entire “unanimity” of the Convention.

As we will see, Madison not only played a leading role in bringing about the Philadelphia Convention (he and Alexander Hamilton orchestrated the report to the Confederation Congress – the Annapolis Report – which made the recommendation that a convention be called in May 1787 in Philadelphia to address the defects of the Articles of Confederation), but he also played a critical supporting role (through his writings) in the debates in the state ratifying conventions, and then a more formal role when ratification seemed to be doomed. The Constitution was “his baby” and he was going to do all he could to see it adopted and a stronger union created. [In September 1786, a conference was called in Annapolis, Maryland to discuss the state of commerce in the fledgling nation. The national government had no authority to regulate trade between and among the states. The conference was called by Virginia, at the urging of Madison, to discuss ways to facilitate commerce and establish standard rules and regulations. Only five of the 13 states sent any delegates at all].

Between November 20, 1787 and January 9, 1788, five states – Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut – ratified the Constitution with relative ease, although the bitter minority report of the Pennsylvania opposition was widely circulated. Despite overwhelming success with these early conventions, the Federalists were well aware of the difficulties that lay ahead. Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Virginia, and New York were still to come and they knew that North Carolina and Rhode Island weren’t going to sign. In other words, the difficult journey still lied ahead because the anti-Federalist (opponents of the proposed Constitution) were aggressively campaigning against ratification, six states were in doubt, and the magic number of 9 states (Article VII – when 9 states ratified the Constitution, it would take effect) might never be achieved.

In the month after the close of the Convention, Madison found himself in New York and with some time to spare. It didn’t look good; too many political heavyweights were lining up against ratification. New York was unlikely to approve the Constitution. When John Lansing and Robert Yates abandoned the Philadelphia Convention, as Gutzman wrote, “they said that they had not been sent to Philadelphia to replace the Confederation with a national government.” New York’s strongest political figure, its Governor, George Clinton, sided with Lansing and Yates. Alexander Hamilton, a delegate to the Convention from NY, advised Madison that the best way to improve the chances of ratification in his state was to appeal directly to the electorate through the newspapers. After all, several anti-Federalists were already writing articles and other publications criticizing the Constitution and condemning the ambitious government it believed it created.

In addition to the anti-Federalist essays written by Governor Clinton (“Cato”), there were other, also powerful, essays published to criticize the Constitution and to highlight its many flaws. There was “Brutus” from New York (likely Robert Yates or Melancton Smith, or maybe even John Williams), “Centinel” from Pennsylvania (Samuel Bryan), “Agrippa” from Massachusetts (James Winthrop), and the “Federal Farmer” from Virginia (most likely Richard Henry Lee, or maybe Mercy Otis Warren). The is no list to identify with certainty which individuals authored the essays. Agrippa published 11 Letters “To the people,” and 5 essays “To the Massachusetts Convention” by February 5. Brutus published 11 of his 16 essays, Cato published all of his 7 essays, Centinel published 14 of his 18 letters, and Federal Farmer published all of his 18 letters between October 1787 and the start of the Massachusetts ratifying convention, which was January 9, 1788. Much to the dismay of the Federalists, the flood of Anti-federalist essays were starting to have their impact on the electorate and on more importantly, on the election of delegates, and key conventions were yet to meet (namely, New York and Virginia). In fact, in both those states, the majority of delegates selected would be anti-Federalists.

[New York would call for its convention on February 1, select its delegates from April 29 to May 3, and set its date for June 17. Virginia would select its delegates in March, and set a date of June 2 for its convention].

Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and prominent NY figure, lawyer John Jay agreed to address the anti-Federalist campaign, convinced that rejection of the Constitution would condemn the states to an unworkable union. It is likely that Madison took charge from the beginning, laying out a theme or roadmap for the essays, making sure that the criticisms of the anti-federalists were addressed, making sure the provisions of the Constitution that were most contentious were addressed and effectively explained, and that the arguments in favor of the Constitution were made that he wanted. When Jay became very ill, the bulk of the essays would have to be split between Hamilton and Madison; Jay would only be able to write 3 essays. The three men responded to each and every one of the criticisms of the anti-Federalist, in essay form, under the pen name “Publius.” Beginning in October 1787, these men penned 85 essays for New York newspapers and later collected them into 2 volumes entitled The Federalist (later to be referred to as The Federalist Papers), which addressed each concern of the anti-Federalists, analyzed the Constitution, detailed the thinking of the framers, anticipated scenarios posed by the critics, and explained what each provision meant. The Federalist Papers gave assurances that the fears of the anti-Federalists were unfounded and mere speculation and conjecture. One reading the Federalist Papers would believe the federal government to be one of strict and limited powers and without any threat of overstepping or abusing its powers. Comparing the government explained in the Federalist Papers to the one today would be to compare a pea to a grapefruit.

In contrast to its predecessor states (Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut), the Massachusetts convention was angry and contentious, and at one point, it erupted into a fistfight between Federalist delegate Francis Dana and anti-Federalist Elbridge Gerry when the latter was not allowed to speak. The impasse was resolved only when revolutionary heroes and leading anti-Federalists Samuel Adams and John Hancock agreed to ratification on the condition that the convention also propose amendments. In other words, Massachusetts’ ratification was a “conditional” one. [The convention’s proposed amendments included a requirement for grand jury indictment in capital cases, which would form part of the Fifth Amendment, and an amendment reserving powers to the states not expressly given to the federal government, which would later form the basis for the Tenth Amendment. Massachusetts’ Ratification is provided in the Appendix at the end of this article].

The next contentious convention would be in Virginia – in June.

At this point, I wanted to provide a timeline of the State Ratifying Conventions:

Timeline of State Ratifying Conventions:

Delaware – December 7, 1787 – Delaware ratified the Constitution, 30-0. [http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/delaware-ratifies-30-0/ ]

Pennsylvania – December 12, 1787 – Pennsylvania ratified, 46-23. [http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/pennsylvania-ratifies-46-23/ ]

New Jersey – December 18, 1787 – New Jersey ratified, 38-0. [http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/new-jersey-ratifies-38-0/ ]

Georgia – December 31, 1787 – Georgia ratified, 20-0. [http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/georgia-deed-of-ratification/ ]

Connecticut – January 9, 1787 – Connecticut ratified 128-40. [http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/connecticut-ratifies-128-40/]

Massachusetts – February 6, 1788 – The delegates to the Massachusetts Ratifying Convention were split on whether to ratify the Constitution or reject it, and so they came up with a compromise. The high road explanation is that responsible leaders from both parties, including Adams and Hancock, convened and said, “Look, we’ve been at this now for nearly a month. We’re not making any progress whatsoever. The country is in crisis and if Massachusetts doesn’t sign, then we’re down the tubes. Is there some way we can come to some common ground on this?” And the common ground was that Massachusetts would ratify now with an expectation that in the First Congress amendments would be proposed to alter the Constitution. This is known as the Massachusetts Compromise. And enough people bought into it because Hancock bought into it, that it swayed enough delegates to ensure ratification. So the high ground is the sense of crisis, the sense of duty, the sense of Hamilton‘s remark in Federalist 85 that states would be better off signing quickly and working within the system, and that sense that Massachusetts had a responsibility to step up and take the lead. Ultimately, the Massachusetts Ratifying Convention ratified 187-168 with 9 proposed amendments – again with the understanding and expectation that a Bill of Rights would be added. [http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/stagethree/ ]

New Hampshire – February 14, 1788 – A majority of the delegates to the New Hampshire Ratifying Convention were opposed to ratification, and so the delegates to the convention voted to postpone until June 18, at which time they would take up the issue of ratification again. [http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/stagethree/ ]

Rhode Island – March 24, 1788 – Rhode Island rejected the call for a state ratifying convention; the state had no intention of even considering a new constitution.

Maryland – April 26, 1788 – Maryland ratified 63-11. [http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/stagefour/#maryland ]

South Carolina – May 23, 1788 – South Carolina ratified, 149-73, with 5 Declarations and Resolves. [http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/tansill/ratification-southcarolina/ ]

New Hampshire – June 21, 1788 – New Hampshire ratified 57-47, with 12 proposed amendments. [http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/new-hampshire-ratifies-57-47-with-12-proposed-amendments/ ]

Virginia – June 25, 1788 – Virginia ratified 89-79, with 20 Bill of Rights and 20 proposed amendments. [http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/virginia-ratifies-89-79-with-20-proposed-amendments/ ]

On July 2, 1788, the Confederation Congress (still under the Articles of Confederation at the time), adopted the ratification of the US Constitution. The old union (13 colonies-turned-states) was dissolved at that point and a new union, comprising the states that had ratified up until this point (DE, PA, NJ, GA, CT, MA, NH, MD, SC, and VA) was formed.

New York – July 25-26, 1788 – New York ratified on July 26, after debating the day before whether to ratify with amendments or not. It ratified by a slim margin, 30-27, with 25 Bill of Rights and 31 proposed amendments. [http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/new-york-ratifies-30-27-with-31-proposed-amendments/ ]. The first three Bill of Rights read:

(1) That all Power is originally vested in and consequently derived from the People, and that Government is instituted by them for their common Interest Protection and Security.

(2) That the enjoyment of Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness are essential rights which every Government ought to respect and preserve.

(3) That the Powers of Government may be reassumed by the People, whensoever it shall become necessary to their Happiness; that every Power, Jurisdiction and right, which is not by the said Constitution clearly delegated to the Congress of the United States, or the departments of the Government thereof, remains to the People of the several States, or to their respective State Governments to whom they may have granted the same; And that those Clauses in the said Constitution, which declare, that Congress shall not have or exercise certain Powers, do not imply that Congress is entitled to any Powers not given by the said Constitution; but such Clauses are to be construed either as exceptions to certain specified Powers, or as inserted merely for greater Caution. [= “RESUMPTION CLAUSE.” This condition to ratification, as the states of Virginia and Rhode Island also exercised this condition, is critical to understanding the reserved right of a state to secede from the Union].

(4) That the People have an equal, natural and unalienable right, freely and peaceably to Exercise their Religion according to the dictates of Conscience, and that no Religious Sect or Society ought to be favored or established by Law in preference of others.

(5) That the People have a right to keep and bear Arms; that a well-regulated Militia, including the body of the People capable of bearing Arms, is the proper, natural and safe defense of a free State;

North Carolina – August 2, 1788 – North Carolina voted 184-84 against ratification. [http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/elliot/vol4/northcarolina0802/ ]

On September 13, 1788, the Confederation Congress prepared for the new government to take its place. On January 7, 1789, presidential electors were selected, and on February 4, the first election was held to select representatives to the new government under the US Constitution. The candidates receiving the top votes for president were George Washington and John Adams, and so they became the country’s first president and vice-president, respectively. James Madison was elected to the first US Congress from the state of Virginia. The first US Congress was inaugurated on March 4, and finally, on March 30, Washington was inaugurated. He delivered what would become one of the most memorable and often-cited Inaugural addresses.

The first government created by the US Constitution was installed.

North Carolina – November 21, 1789 – North Carolina ratified 194-77, with 20 Bill of Rights and 21 proposed amendments

Rhode Island – May 29, 1790 – Rhode Island ratified 34-32, with 18 Bill of Rights and 21 proposed amendments. [Reference: http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/tansill/ratification-rhodeisland/ ]

*** Timeline of Ratification of the US Constitution, Reference: http://teachingamericanhistory.org/bor/timeline/. By clicking on the State Ratifying Convention, you can pull up the debates, the votes, and the proposed amendments associated with each state’s vote. Also, I have included, in the Appendix at the end of this article, the proposed Bill of Rights and/or proposed amendments proposed by the certain states in their ratifications].

—————————————————————

Having co-written The Federalist Papers to help secure ratification in New York, James Madison left the state for Virginia, to take up the battle there. [The Virginia Convention would be held before the New York Convention, two weeks before, but as it turned out, they would continue simultaneously]. Back in Virginia, Madison would have to face Patrick Henry, George Mason, Edmund Randolph, James Monroe, Richard Henry Lee (one-time president of the Continental Congress) and William Grayson (VA representative in the Continental Congress). George Mason had authored the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights and the state constitution (chief author, at least) so he would clearly be a forceful authority on the necessity of a Bill of Rights. Mason and Lee would mount the most strenuous opposition to the proposed Constitution, in favor of amending it to include a Bill of Rights. Patrick Henry would oppose it on states’ rights grounds as well. He urged that Virginia hold out for amendments.

Virginia elected its delegates to the Convention in March 1788, and many men – many prominent men – ran for a seat. Interestingly, some of the more prominent men who chose not to run, or who did not win, included George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Beverley Randolph, Richard Henry Lee, and a few others. The most prominent men who were elected included James Madison, Patrick Henry, George Mason, Governor Edmund Randolph, James Monroe, William Grayson, Edmund Pendleton, George Wythe, George Nicholas, former VA Governor Benjamin Harrison V, and John Marshall (who would go on to become our most influential Supreme Court Chief Justice). Of the 168 delegates, the majority were anti-Federalists.

In his book James Madison and the Making of America, Gutzman goes into detail with respect to Mason’s objections to the proposed Constitution. He wrote:

On October 7, Mason sent a letter to [George] Washington including his objections to the Constitution. An amended version of notes he had made during the Philadelphia Convention, this document essentially repeated complaints Mason had raised then: There was no Declaration of Rights, and the Supremacy Clause meant state declarations would be unavailing; the House was too small; the Senate had money powers, although it did not represent the people; the combination of legislative and executive powers in the Senate endangered liberty’ the federal judiciary would swallow up the state judiciaries and thus allow the rich to oppress the poor; the president lacked an executive council, which meant he would be led by the Senate; and the vice-president, in limbo between the Senate and the executive branch, was a dangerous personage – besides which he would give one state three Senate votes, which was unfair.

In addition to these objections, Mason also went public with his Philadelphia Convention prediction that the Commerce Clause would empower the eight northern states to abuse the five southern ones. There would be a tendency for Congress to read almost anything into the Necessary & Proper Clause, which threatened both states’ rights and individuals’ rights. [James Madison and the Making of America, pg. 189]

Virginia’s Convention met from June 2 – June 27. The Convention would end up pitting Patrick Henry against James Madison, with the former spending much more time on the floor speaking. Henry was Madison’s most formidable antagonist in the ratification fight. Henry was perhaps our most passionate founding father, being known for his fiery speeches and his imagery. He was the voice of the revolution. As Gutzman wrote: “He was the great guardian of Virginians’ self-government and inherited rights. He was also an orator without parallel, one who could cause hair to stand up on the necks even of his most devout opponents.” He did not disappoint at the Convention.

On June 8, he took to the floor to accuse the proposed government created by the Constitution of being a consolidated one. His position was that a confederated government (under the Articles) was being replaced by a consolidated government. He objected to the introductory phrase “We the People…,” claiming that it conjured up the notion that the government would be a consolidated national one. He wanted the language changed to “We the States…” In his speech that day, he said:

“It is said eight States have adopted this plan. I declare that if twelve States and a half had adopted it, I would, with manly firmness, and in spite of an erring world, reject it. You are not to inquire how your trade may be increased, nor how you are to become a great and powerful people, but how your liberties can be secured; for liberty ought to be the direct end of your Government. Having premised these things, I shall, with the aid of my judgment and information, which, I confess, are not extensive, go into the discussion of this system more minutely. Is it necessary for your liberty that you should abandon those great rights by the adoption of this system? Is the relinquishment of the trial by jury and the liberty of the press necessary for your liberty? Will the abandonment of your most sacred rights tend to the security of your liberty? Liberty, the greatest of all earthly blessings-give us that precious jewel, and you may take every thing else: But I am fearful I have lived long enough to become an fellow: Perhaps an invincible attachment to the dearest rights of man, may, in these refined, enlightened days, be deemed old fashioned: If so, I am contented to be so: I say, the time has been when every pore of my heart beat for American liberty, and which, I believe, had a counterpart in the breast of every true American: But suspicions have gone forth-suspicions of my integrity-publicly reported that my professions are not real. 23 years ago was I supposed a traitor to my country; I was then said to be the bane of sedition, because I supported the rights of my country: I may be thought suspicious when I say our privileges and rights are in danger.”

One of the more contentious days came on June 24; the Convention was winding down. George Wythe opened the day’s proceedings with a speech in favor of ratifying the Constitution before amending it. Madison followed, emphasizing many of the same themes he and Hamilton and Jay had addressed in The Federalist essays. Just as the elderly Benjamin Franklin had urged his fellow delegates in Philadelphia to quit their bickering and work together for the greater good at, Madison essentially tried to make the same point in Richmond. As to the position that amendments should be added before Virginia ratified, Madison argued that it was unreasonable. He didn’t think it was reasonable to expect the other states (eight of them) to retract their unconditional ratifications in order to accommodate Virginia’s demand that the Constitution be first amended, and particularly to include a Bill of Rights. Up until that point, Madison had remained relatively quiet at the Convention. And even when he spoke, he came across as meek. But he was never one to project very well. When he spoke on the 24th, it was in a strained, quiet tone. But he spoke articulately and rationally, and he addressed the many concerns of the anti-Federalists.

When he concluded, he yielded the floor to Henry. From Gutzman’s book:

An account given by Federalist Archibald Stuart proves the point. Henry concluded his speech by calling attention to ‘the awful dangers” attendant upon their vote. “I see beings of a higher order, Henry thundered, “anxious concerning our decision.” “Our own happiness alone is not affected by the event – All nations are interested in the determination. We have it in our power to secure the happiness of one half of the human race….” [James Madison and the Making of America, pg. 233]

The Convention was getting ready to take a vote when an obscure delegate endorsed Patrick Henry’s call for a list of amendments. “The delegate said that he could not vote for ratification until he was assured that amendments protecting Virginians’ historic rights would be recommended. Madison answered that he would not oppose any ‘safe’ amendments (but continued to assert that he believed it unnecessary, and perhaps even dangerous.’” [Ibid, pg. 235]

Ultimately, on June 25, the delegates voted against first proposing amendments to the other states prior to Virginia’s ratification (ie, having the other states recall their unconditional ratification and re-consider ratification after amendments were added) and voted 89-79 in favor of ratification, with proposed amendments. On June 27, the Convention adopted a set of 40 proposed amendments. A committee, headed by law professor George Wythe, drafted the amendments – 20 enumerated individual rights (Bill of Rights) and the other 20 enumerated states’ rights. The amendments were forwarded to the Confederation Congress. [Virginia’s Ratification is provided in the Appendix at the end of this article. Take note of its Bill of Rights – it includes a “Resumption Clause”].

While there were delegates at several conventions who supported an “amendments before” approach to ratification, it soon shifted to an “amendments after” for the sake of trying to hold the Union together. Ultimately, only North Carolina and Rhode Island waited for amendments from Congress before ratifying.

Four days prior to the conclusion of the Virginia Convention, on June 21, 1788, New Hampshire ratified the Constitution. What makes that date special is that when New Hampshire ratified, with its 12 proposed amendments, the required number of state ratifications, according to Article VII of the Constitution, had been met to establish the Constitution. [Article VII – “The ratification of the conventions of nine states, shall be sufficient for the establishment of this Constitution between the states so ratifying the same.”} The Constitution would become operational. A new union (comprised of those states that had ratified) was created and the new frame of government would be established.

The New York ratification convention met on June 17, 1788, while the Virginia Convention was still debating ratification. As with Virginia, a majority of its 67 delegates were anti-Federalists. (The New York Convention would last over month – from June 17 until July 26). On the opening day, the anti-Federalists, led by Governor Clinton, clamored for a Bill of Rights and fought to preserve the autonomy of the state against what it believed were actual and potential federal encroachments. Hamilton (the only NY delegate to the Philadelphia Convention to sign the Constitution) and the Federalists, on the other hand, contended that a stronger central government would provide a solid base from which New York could grow and prosper. While the debates were contentious, the Federalists were ultimately successful and on July 26, the Constitution was ratified by a very slim margin, 30-27, but with 25 Bill of Rights and 31 proposed amendments. The Convention also voted to call for a second federal convention. [New York’s Ratification is provided in the Appendix at the end of this article. Take note of its Bill of Rights – it includes a “Resumption Clause”].

On September 13, 1788, the Articles of Confederation Congress certified that the new Constitution had been ratified by more than enough states for the new system to be implemented and directed the new government to meet in New York City on the first Wednesday in March the following year. On March 4, 1789, the new frame of government came into force with eleven of the thirteen states participating – and without a Bill of Rights.

Opposition to the new Constitution among leading Virginians lingered. It would continue to be a thorn in James Madison’s ass… the man who deceived the states into sending delegates to Philadelphia believing they were tasked with proposing amendments to the Articles of Confederation (when all along, he wanted them to take up the issue of an all-new scheme of government – his scheme, the “Virginia Plan”), the man who thought his scheme had finally been realized, and the man who supposedly held that “not a letter of the Constitution” should be altered.

After Virginia’s ratification and New York’s ratification, the future of the Constitution, as ratified, was not certain. New York wanted to call another federal convention (to amend the new Constitution? To get rid of the new Constitution?) and several powerful Virginians, with Patrick Henry taking the lead, seemed likely to move for the same.

As fate would have it, Madison set his sights on the US Senate. But there was one problem for him – the Constitution (pre-17th Amendment) empowered the state legislatures to elect senators, but the VA state legislature (VA General Assembly) was comprised of many enemies he had made in his efforts to deceive the states at the Philadelphia Convention, to write the Constitution, and to secure its ratification, including the great Patrick Henry. And Henry and his fellow anti-Federalists got the chance to get even: in its selection of Senators, the legislature chose Richard Henry Lee and William Grayson.

Both Richard Henry Lee and William Grayson agreed with Patrick Henry that the Constitution should have been amended to include a Bill of Rights (at the least) before it was ratified. Both, it seems, would favor a second convention.

Madison, at this point, was warming somewhat to the notion of amendments, but it’s not sure if he was warming because he agreed that a Bill of Rights is essential to limit powers of government or if he was just nervous that the issue might be the one to sink his Constitution. One thing is for certain though, he would have rather the Constitution be amended by the first option in Article V (amendments proposed by Congress and then sent to the states for adoption) than by a second convention (the second option in Article V; a convention of states). Kevin Gutzman addressed this in his book:

For one thing, some states would oppose a convention so strongly that they would reflexively oppose any amendment it might propose. For another, it would be easier to have Congress propose amendments than to follow the process in Article V of the Constitution for convening another meeting like the one at Philadelphia. Finally, another convention would include members with extreme views on both ends of the political spectrum, enflame the public mind, and produce nothing conductive to the general good. He had seen how the first convention had worked, and he did not want to hazard a second – which, too, would undermine the impression of the American republic’s stability left in European capitals by the success of the recent ratification campaign. [James Madison and the Making of America, pg. 241]

Defeated in his bid for the US Senate, Madison decided to stand for the House of Representatives. But again, he would be at the mercy of his nemesis, Patrick Henry. Henry wielded power in the General Assembly, and that power included the ability to draw congressional districts. To spite Madison, he helped draw a map that put Montpelier (Madison’s home) in the same district as James Monroe’s house. In the Richmond Convention, Monroe had aligned himself with Henry, Mason, and Grayson and had voted “nay” on the vote for ratification. “Because Monroe had been an authentic hero in the revolution – suffering a significant wound in Washington’s great victory at Trenton – and had established a respectable legislative record in both Virginia and in the Congress of the Confederation, his opposition would be formidable.” [Ibid, pg. 241]

Madison campaigned against Monroe, and due to the contentious issue of the Constitution lacking a Bill of Rights, Madison softened on the issue of adding amendments. Perhaps all the letters that Jefferson sent him at this time emphasizing the need for a Bill of Rights had something to do with it. “If pursued with a proper moderation and in a proper mode [meaning that the First Congress would propose amendments for the states’ approval, per Article V], they would serve the double purpose of satisfying the minds of well-meaning opponents and of providing additional guards in favor of liberty.” [Ibid, pg. 242]. Taking Madison at his word and believing him to be a man of his word, voters selected him over Monroe for the US House of Representatives.

On March 4, 1789, the first US Congress was seated, in New York City’s Federal Hall. The first thing to do was to organize itself. On April 1, the House of Representatives elected its officers, and the Senate did the same on April 6. Also on the 6th, the House and Senate met in joint session and counted the Electoral College ballots for the selection of president. George Washington was certified as president (having been unanimously selected) and John Adams as vice president.

On April 30, 1789, George Washington was inaugurated as the nation’s first president, also at Federal Hall, delivering the Inaugural Address that James Madison had written for him. In that message, Washington addressed the subject of amending the Constitution. He urged the legislators:

“Whilst you carefully avoid every alteration which might endanger the benefits of an united and effective government, or which ought to await the future lessons of experience; a reverence for the characteristic rights of freemen, and a regard for public harmony, will sufficiently influence your deliberations on the question, how far the former can be impregnably fortified or the latter be safely and advantageously promoted…..”

Madison knew that as long as the concerns of the anti-Federalists regarding the Constitution remained unaddressed, the threat of a new convention would remain, and so he would take the initiative to propose amendments (comprising a Bill of Rights) himself. By taking the initiative to propose amendments himself through the Congress, he hoped to preempt a second constitutional convention that might, it was feared, undo the difficult compromises of 1787, and open the entire Constitution to reconsideration, thus risking the dissolution of the new federal government. Writing to Jefferson, he stated, “The friends of the Constitution, some from an approbation of particular amendments, others from a spirit of conciliation, are generally agreed that the System should be revised. But they wish the revisal to be carried no farther than to supply additional guards for liberty.” He also felt that amendments guaranteeing personal liberties would “give to the Government its due popularity and stability.” Finally, he hoped that the amendments “would acquire by degrees the character of fundamental maxims of free government, and as they become incorporated with the national sentiment, counteract the impulses of interest and passion.” [Historians continue to debate the degree to which Madison considered the amendments of the Bill of Rights necessary, and to what degree he considered them politically expedient; in the outline of his address, he wrote, “Bill of Rights—useful—not essential—”]. (see Wikipedia)

On June 8, Madison introduced a series of Constitutional amendments in the House of Representatives for consideration. Among his proposals was one that would have added introductory language stressing natural rights to the Preamble. Another would apply parts of the Bill of Rights to the states as well as the federal government. Several sought to protect individual personal rights by limiting various Constitutional powers of Congress. He urged Congress to keep the revision to the Constitution “a moderate one,” limited to protecting individual rights.

Madison was deeply read in the history of government and used a range of sources in composing the amendments. The English Magna Carta inspired the right to petition and to trial by jury, for example, while the English Bill of Rights of 1689 provided an early draft for the right to keep and bear arms and also for the right against cruel and unusual punishment.

The greatest influence on Madison’s text, however, was existing state constitutions, and especially Virginia’s. Many of his amendments, including his proposed new preamble, were based on the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which were drafted in 1776 by another great nemesis, anti-Federalist George Mason. To reduce future opposition to ratification, Madison also looked for recommendations shared by many states. He did provide one, however, that no state had specifically requested: “No state shall violate the equal rights of conscience, or the freedom of the press, or the trial by jury in criminal cases.” He did not include an amendment that every state had asked for, one that would have made tax assessments voluntary instead of contributions. Madison’s proposed the following constitutional amendments:

First. That there be prefixed to the Constitution a declaration, that all power is originally vested in, and consequently derived from, the people.

That Government is instituted and ought to be exercised for the benefit of the people; which consists in the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the right of acquiring and using property, and generally of pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

That the people have an indubitable, unalienable, and indefeasible right to reform or change their Government, whenever it be found adverse or inadequate to the purposes of its institution.

Secondly. That in article 1st, section 2, clause 3, these words be struck out, to wit: “The number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty thousand, but each State shall have at least one Representative, and until such enumeration shall be made;” and in place thereof be inserted these words, to wit: “After the first actual enumeration, there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand, until the number amounts to—, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that the number shall never be less than—, nor more than—, but each State shall, after the first enumeration, have at least two Representatives; and prior thereto.”

Thirdly. That in article 1st, section 6, clause 1, there be added to the end of the first sentence, these words, to wit: “But no law varying the compensation last ascertained shall operate before the next ensuing election of Representatives.”

Fourthly. That in article 1st, section 9, between clauses 3 and 4, be inserted these clauses, to wit: The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext, infringed.

The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.

The people shall not be restrained from peaceably assembling and consulting for their common good; nor from applying to the legislature by petitions, or remonstrances for redress of their grievances.

The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed; a well-armed and well-regulated militia being the best security of a free country: but no person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms shall be compelled to render military service in person.

No soldier shall in time of peace be quartered in any house without the consent of the owner; nor at any time, but in a manner warranted by law.

No person shall be subject, except in cases of impeachment, to more than one punishment, or one trial for the same offence; nor shall be compelled to be a witness against himself; nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor be obliged to relinquish his property, where it may be necessary for public use, without a just compensation.

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

The rights of the people to be secured in their persons, their houses, their papers, and their other property, from all unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated by warrants issued without probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, or not particularly describing the places to be searched, or the persons or things to be seized.

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, to be informed of the cause and nature of the accusation, to be confronted with his accusers, and the witnesses against him; to have a compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor; and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.

The exceptions here or elsewhere in the Constitution, made in favor of particular rights, shall not be so construed as to diminish the just importance of other rights retained by the people, or as to enlarge the powers delegated by the Constitution; but either as actual limitations of such powers, or as inserted merely for greater caution.

Fifthly. That in article 1st, section 10, between clauses 1 and 2, be inserted this clause, to wit: No State shall violate the equal rights of conscience, or the freedom of the press, or the trial by jury in criminal cases.

Sixthly. That, in article 3d, section 2, be annexed to the end of clause 2d, these words, to wit: But no appeal to such court shall be allowed where the value in controversy shall not amount to — dollars: nor shall any fact triable by jury, according to the course of common law, be otherwise re-examinable than may consist with the principles of common law.

Seventhly. That in article 3d, section 2, the third clause be struck out, and in its place be inserted the clauses following, to wit: The trial of all crimes (except in cases of impeachments, and cases arising in the land or naval forces, or the militia when on actual service, in time of war or public danger) shall be by an impartial jury of freeholders of the vicinage, with the requisite of unanimity for conviction, of the right with the requisite of unanimity for conviction, of the right of challenge, and other accustomed requisites; and in all crimes punishable with loss of life or member, presentment or indictment by a grand jury shall be an essential preliminary, provided that in cases of crimes committed within any county which may be in possession of an enemy, or in which a general insurrection may prevail, the trial may by law be authorized in some other county of the same State, as near as may be to the seat of the offence.

In cases of crimes committed not within any county, the trial may by law be in such county as the laws shall have prescribed. In suits at common law, between man and man, the trial by jury, as one of the best securities to the rights of the people, ought to remain inviolate.

Eighthly. That immediately after article 6th, be inserted, as article 7th, the clauses following, to wit: The powers delegated by this Constitution are appropriated to the departments to which they are respectively distributed: so that the Legislative Department shall never exercise the powers vested in the Executive or Judicial, nor the Executive exercise the powers vested in the Legislative or Judicial, nor the Judicial exercise the powers vested in the Legislative or Executive Departments.

The powers not delegated by this Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the States respectively.

Ninthly. That article 7th, be numbered as article 8th.

[References: See the Appendix, at the end of this article, for James Madison’s Speech in the House of Representatives, June 8, 1789, proposing a Bill of Rights, and also see Wikipedia: “United States Bill of Rights”].

The House passed a joint resolution containing 17 amendments based on Madison’s proposal. The Senate changed the joint resolution to consist of 12 amendments and rejected Madison’s suggestions for the Preamble. A joint House and Senate Conference Committee settled remaining disagreements in September. On October 2, 1789, President Washington sent copies of the 12 amendments adopted by Congress to the states. Again, the states would have to call up conventions – this time to debate and ratify the proposed amendments.

In the meantime, North Carolina finally ratified the Constitution, 194-77, with 20 Bill of Rights and 21 proposed amendments. She remained true to her principles – that she would not ratify a constitution without a Bill of Rights included. Note that while North Carolina was second to last to ratify the Constitution, she was third to ratify the Bill of Rights, on December 22, 1789).

On December 15, Virginia was the eleventh state to adopt the amendments. Having been adopted by the requisite three-fourths of the several states (there being 14 States in the Union at the time, as Vermont had been admitted into the Union on March 4, 1791), the ratification of Articles Three through Twelve was completed and they became Amendments 1 through 10 of the Constitution – also known as our US Bill of Rights. President Washington informed Congress of this on January 18, 1792.

The original First and Second amendments fell short of the required 3/4 majority to make it into the Constitution, but interestingly, the original proposed second amendment (which addressed when Congress can change its pay) finally was adopted in 1992 to become our last amendment, the 27th amendment.

Note that the US Bill of Rights applies only to action by the federal government. It places limits only on its power. As most of you may know from your state constitutions, states have included similar guarantees of liberty of their own. Article I of the North Carolina State Constitution, for example, lists the NC Bill of Rights. The 14th Amendment has been mis-applied to incorporate all guarantees of rights and privileges on the states, and in fact, the 14th amendment, even though it was never constitutionally ratified, is the number one basis for all constitutional challenges.

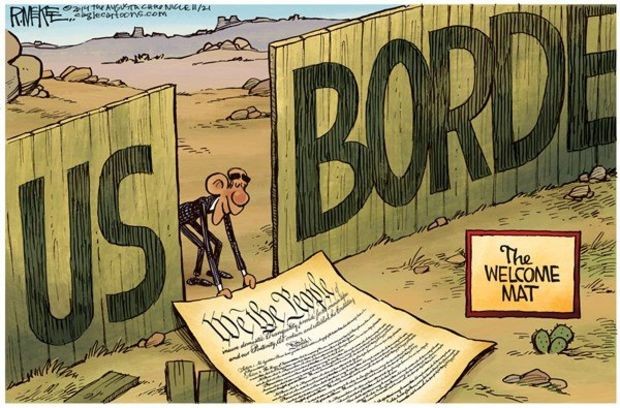

It is a shame that the cartoon depiction of the Bill of Rights attached leaves off the 9th and 10th Amendments. The 9th Amendment states that the enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people. And the 10th Amendment states that all powers not expressly delegated to the federal government by the Constitution nor prohibited by it to the states are reserved to the states or to the people. These amendments underscore the unique foundation of American liberty – that government is not the ultimate sovereign and individuals enjoy only those rights and privileges the government is generous enough to grant them. In America, rights are endowed on each individual by the Creator, inseparable from our very humanity, and government power derives from the natural and inherent right of each person to govern himself and to protect himself, his family, and his property. This is the concept of Individual Sovereignty referred to in the Declaration of Independence, the document that provides the foundational principles, the rights, and expectations for each State in this Union (despite what the federal government might say). It is the document that recognized each state as an independent sovereign for the world to take note; it is the document for which the Treaty of Paris of 1783 addressed to end the war for American Independence. The treaty included this provision: “Britain acknowledges the United States (New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia[15]) to be free, sovereign, and independent states….. “

James Madison wrote: “In Europe, charters of liberty have been granted by power. America has set the example … of charters of power granted by liberty. This revolution in the practice of the world, may, with an honest praise, be pronounced the most triumphant epoch of its history, and the most consoling presage of its happiness.”

I urge everyone to take time today and read the Bill of Rights and understand what each guarantees and why. After all, they protect your most essential liberty rights.

References:

Kevin R.C. Gutzman, James Madison and the Making of America; St. Martin’s Press (NY), 2012.

Gordon Lloyd, “The Bill of Rights,” Teaching American History. Referenced at: http://teachingamericanhistory.org/bor/roots-chart/

The Six Stages of Ratification – Stage III: Winter in New England: Postpone and Compromise (Massachusetts – February 6, 1788 and New Hampshire (postpones) – February 24, 1788) –http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/stagethree/

Report of the House Select Committee, July 28, 1789 – http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/report-of-the-house-select-committee/

House Debates Select Committee Report, August 13-24, 1789 – http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/house-debates-select-committee-report/

Ratification of the Constitution, State-by-State – http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/overview/

US Constitution, Virginia’s Ratification, from the Library of Congress (from its copy of Elliot’s Debates) – https://www.usconstitution.net/rat_va.html

Day-to-Day Summary of the Virginia Ratifying Convention – http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/virginiatimeline/ OR http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/virginia/

US Constitution, New York’s Ratification, from the Library of Congress (from its copy of Elliot’s Debates) – https://www.usconstitution.net/rat_ny.html

Day-to-Day Summary of the New York Ratifying Convention – http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/newyorktimeline/ OR: http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/newyork/

The Debates in the Several State Ratifying Conventions (Elliott’s Debates) – http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/elliot/ [On this site, you can click on links for the following state conventions and it will bring you to calendars so you can see what they did on a day-by-day basis: Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina]

James Madison Proposes a Bill of Rights to Congress, June 8, 1789) – http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/documents/1786-1800/madison-speech-proposing-the-bill-of-rights-june-8-1789.php

United States Bill of Rights,” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Bill_of_Rights

Patrick Henry’s Speech at the Virginia Ratifying Convention, June 8, 1788 – http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/documents/1786-1800/the-anti-federalist-papers/speech-of-patrick-henry-(june-5-1788).php

Letter from Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, dated December 20, 1787, Founders Online – https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-12-02-0454

Chart: Approval of the Bill of Rights in Congress and the States — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Bill_of_Rights

APPENDIX #1 (Letter from Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, dated December 20, 1787, on the topic of the new Constitution and the lack of a Bill of Rights)

“…….I have little to fill a letter. I will therefore make up the deficiency by adding a few words on the Constitution proposed by our Convention. I like much the general idea of framing a government which should go on of itself peaceably, without needing continual recurrence to the state legislatures. I like the organization of the government into Legislative, Judiciary and Executive. I like the power given the Legislature to levy taxes; and for that reason solely approve of the greater house being chosen by the people directly. For though I think a house chosen by them will be very ill-qualified to legislate for the Union, for foreign nations etc. yet this evil does not weigh against the good of preserving inviolate the fundamental principle that the people are not to be taxed but by representatives chosen immediately by themselves. I am captivated by the compromise of the opposite claims of the great and little states, of the latter to equal, and the former to proportional influence. I am much pleased too with the substitution of the method of voting by persons, instead of that of voting by states…. There are other good things of less moment. I will now add what I do not like. First the omission of a bill of rights providing clearly and without the aid of sophisms for freedom of religion, freedom of the press, protection against standing armies, restriction against monopolies, the eternal and unremitting force of the habeas corpus laws, and trials by jury in all matters of fact triable by the laws of the land and not by the law of Nations. To say, as Mr. Wilson does that a bill of rights was not necessary because all is reserved in the case of the general government which is not given, while in the particular ones all is given which is not reserved might do for the Audience to whom it was addressed, but is surely gratis dictum, opposed by strong inferences from the body of the instrument, as well as from the omission of the clause of our present confederation which had declared that in express terms. It was a hard conclusion to say because there has been no uniformity among the states as to the cases triable by jury, because some have been so incautious as to abandon this mode of trial, therefore the more prudent states shall be reduced to the same level of calamity. It would have been much more just and wise to have concluded the other way that as most of the states had judiciously preserved this palladium, those who had wandered should be brought back to it, and to have established general right instead of general wrong. Let me add that a bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inference……”

[Reference: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-12-02-0454 ]

APPENDIX #2 (James Madison’s Speech in Congress, June 8, 1789, proposing a Bill of Rights)

I am sorry to be accessary to the loss of a single moment of time by the house. If I had been indulged in my motion, and we had gone into a committee of the whole, I think we might have rose, and resumed the consideration of other business before this time; that is, so far as it depended on what I proposed to bring forward. As that mode seems not to give satisfaction, I will withdraw the motion, and move you, sir, that a select committee be appointed to consider and report such amendments as are proper for Congress to propose to the legislatures of the several States, conformably to the 5th article of the constitution.

I will state my reasons why I think it proper to propose amendments; and state the amendments themselves, so far as I think they ought to be proposed. If I thought I could fulfil the duty which I owe to myself and my constituents, to let the subject pass over in silence, I most certainly should not trespass upon the indulgence of this house. But I cannot do this; and am therefore compelled to beg a patient hearing to what I have to lay before you. And I do most sincerely believe that if congress will devote but one day to this subjects, so far as to satisfy the public that we do not disregard their wishes, it will have a salutary influence on the public councils, and prepare the way for a favorable reception of our future measures.

It appears to me that this house is bound by every motive of prudence, not to let the first session pass over without proposing to the state legislatures some things to be incorporated into the constitution, as will render it as acceptable to the whole people of the United States, as it has been found acceptable to a majority of them. I wish, among other reasons why something should be done, that those who have been friendly to the adoption of this constitution, may have the opportunity of proving to those who were opposed to it, that they were as sincerely devoted to liberty and a republican government, as those who charged them with wishing the adoption of this constitution in order to lay the foundation of an aristocracy or despotism. It will be a desirable thing to extinguish from the bosom of every member of the community any apprehensions, that there are those among his countrymen who wish to deprive them of the liberty for which they valiantly fought and honorably bled. And if there are amendments desired, of such a nature as will not injure the constitution, and they can be ingrafted so as to give satisfaction to the doubting part of our fellow citizens; the friends of the federal government will evince that spirit of deference and concession for which they have hitherto been distinguished.